From Russia’s threat of nuclear weapons to the patriotic courage of Volodymyr Zelenskiy, an A to Z of how the world has changed

- Russia-Ukraine war: latest news

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been described by politicians and commentators as a watershed moment in modern history, a turning point comparable in importance to the 9/11 attacks in the US in 2001, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and even the assassination of John F Kennedy in 1963.

Whether this portentous view of the war turns out to be justified, only time – and future historians – will tell. But there’s no doubt that in the violent, tumultuous days after 24 February, the established international order has been shaken and, in some respects, upended in extraordinary, unexpected and often unwelcome ways.

Ukraine – a country at the crossroads of Europe and Asia that is little known and often ignored – has become overnight the crucible of a new world order, a catalyst and trigger for radical upheaval. It has produced a new geopolitical alphabet, spelling out a much-altered future.

A

Atomic weapons Vladimir Putin’s ill-disguised threat to go nuclear should the west intervene to halt the invasion has come scarily close to breaking a post-1945 taboo. It has undoubtedly inhibited the US and British response, with fears expressed about a “third world war”. A dangerous precedent has been set.

B

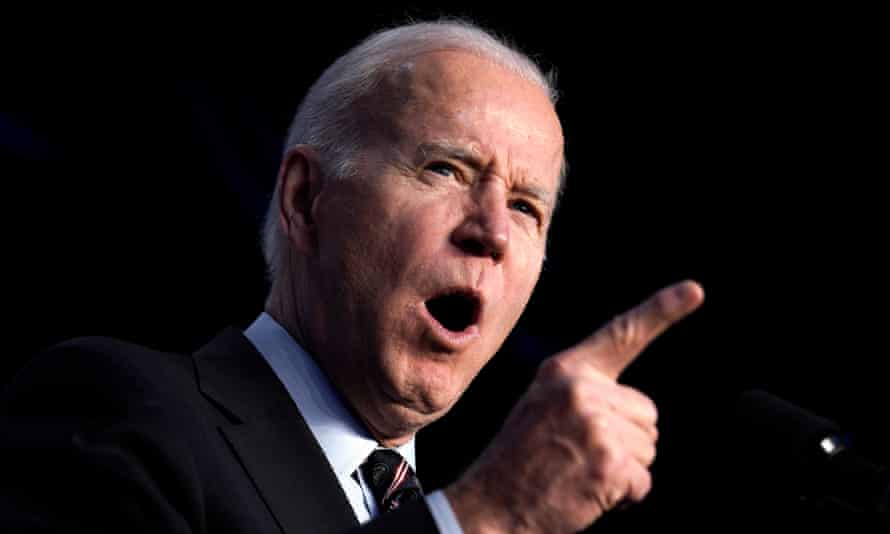

Joe Biden’s tenure as US president may be fatally undermined by the war. He is praised for avoiding direct military confrontation with Russia. But as in Afghanistan last year, he has failed to prevent a humanitarian disaster – or stop Putin. Anger over resulting domestic energy price rises and retail inflation could be his undoing.

C

China stands to be the big strategic winner if, as seems likely, Ukraine becomes a protracted trial of strength between Russia and the west. Its president, Xi Jinping, appears to have given Putin a green light when they met just before the invasion. Now he’s backing peace efforts. China’s economy has been hurt by rising commodity costs. But it’s a small price to pay for increased global dominance.

D

Disinformation used as a weapon of war, particularly in the form of “false flag” operations, invented social media “facts”, and internet bots, has come of age in the Ukraine conflict. When coupled with cyber warfare, propaganda, media manipulation and rigid censorship, as in Russia, it’s a potent means of sowing doubt, division and defeatism.

E

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey’s unpopular authoritarian president and serial invader of Syria and Iraq, is one of several unlikely would-be peacemakers. Erdoğan has bought missiles from Russia, sold drones to Ukraine, and his country belongs to Nato. Perhaps that’s why no one trusts him. High-level talks last week in Turkey were a Russian time-wasting exercise. But by hosting them, Erdoğan hopes for a boost before difficult elections next year.

F

France’s Emmanuel Macron appears to have added critical impetus to his presidential re-election bid next month through his dogged efforts to keep Putin engaged in some sort of dialogue. In contrast, far-right hopefuls Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour have been forced to defend their Russian ties.

G

Germany’s chancellor, Olaf Scholz shocked friends and enemies alike shortly after the invasion by suspending the highly prized Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia and creating an £85bn fund to boost the country’s armed forces. For the first time since the Nazi era, Germany has begun to re-arm – and Europe cheered. Extraordinary.

H

Hunger, and consequent political unrest, affecting poorer countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia is a growing fear as Ukraine’s and Russia’s wheat, grain and vegetable oil exports are cut off. In Tunisia, symbolic birthplace of the Arab spring revolts, bread prices recently hit an unsustainable 14-year high.

I

Israel has disappointed its friends with its invasion fence-sitting, ostensibly justified by a need to keep on terms with Russia in Syria. But its rightwing government will be happy if the war scuppers the west’s proposed revived nuclear deal with Iran, to which the ever devious Putin has suddenly raised fresh objections.

J

Boris Johnson, Britain’s prime minister, was on the ropes and almost out for the count in the days before the invasion, vilified for illegal Downing Street partying in breach of Covid lockdown rules. But the war, allowing him to play international statesman, has provided a new lease of political life – for now.

K

Kaliningrad, the Russian enclave squeezed between Poland and Lithuania, and the three (former Soviet) Baltic republics are emerging as possible next flashpoints. Fabricated fears about the safety of ethnic Russians in Estonia, for example, have been used in the past to justify Putin’s threats, just like in Ukraine. Now they are being whipped up again.

L

International law has taken a battering from which it may not recover. By its actions, Russia has torn up the UN charter. Yet the UN security council is powerless to act in the face of Moscow’s permanent veto power – which it used to block a resolution condemning the invasion. Russia also boycotted a hearing on Ukraine at the UN’s highest court, the international court of justice in The Hague. UN reform must come soon.

M

Emmanuel Macron’s oft-mocked vision of a sovereign Europe that enjoys “strategic autonomy” and its own military and security capabilities independent of the US has been boosted by the war. Rattled EU leaders meeting at last week’s Versailles summit agreed Europe urgently needed to be better able to defend itself.

N

Nato has emerged united and stronger, so far, and there is talk of Finland and Sweden joining (though not Ukraine). But the 30-country, US-led alliance is facing criticism for not doing more to help Kyiv. And the war has revived debate over whether Nato’s eastward enlargement after the Soviet collapse was a blunder that contributed to the current crisis.

O

Oil and gas are fatal chinks in western armour when confronting Russia. The US and Britain decided last week to ban all oil imports by year’s end. The heavily dependent EU needs more time. But rocketing prices, hitting businesses and consumers, have dramatised how hugely powerful a weapon energy is for Putin. A race to find badly needed “green” and nuclear alternatives has begun.

P

Playing and watching international sport has got a lot harder – if you are Russian. The country’s athletes, footballers, and racing drivers are among sportspeople banned from European and world competitions. Boycotts have a cultural aspect, too, involving ballet, theatre, orchestras and even cat lovers. Such unprecedented “virtue signalling” may backfire, by convincing ordinary Russians that they, not just their government, are being targeted.

Q

The quest for truth – the fundamental purpose of free, independent media – has been further set back by the war. Russia has long persecuted western correspondents. Now it is threatening them with prison if they report openly on the invasion. Facebook and Twitter have been blocked. The EU, in turn, has banned Russian state-backed RT and Sputnik, deeming them mere propaganda outlets. The concept of the freedom of the press is under siege.

R

Record refugee outflows, and an accompanying humanitarian crisis, may overwhelm the ability of EU governments and relief agencies to cope. More than 2 million Ukrainians have fled so far, from a population of 44 million. Europe opened its borders amid an epic outpouring of public support. But the EU’s longstanding lack of an agreed, collective refugee policy, and Britain’s shamefully mean-spirited response, suggest trouble ahead as the numbers grow.

S

Sanctions on Russia are the most sweeping and punitive ever imposed. Banks, including Russia’s central bank, businesses and oligarchs have been hit hard. The rouble has plunged. Numerous western brands and companies such as Shell have pulled out. So far Putin has shrugged it off, but this looks like a bluff. If Russia defaults, or retaliates by cutting gas supplies to Europe, the result may be an all-round economic meltdown, big job losses, and a drastic fall in living standards in the UK and elsewhere.

T

Taiwan has been watching events in Ukraine with deep unease. The US refusal to come to Kyiv’s aid with direct military support is especially chilling, given the invasion threat the island faces from Beijing. As with Ukraine, Washington has no legal or treaty obligation to fight for Taiwan. Its position is deliberately ambiguous – and inherently unreliable. China is watching, too.

U

The United Arab Emirates is among several western allies in the Middle East and Asia that have failed to show hoped-for solidarity. The UAE has not condemned the invasion, nor has it adopted sanctions against Russia, with which it has close financial ties. Mealy mouthed Narendra Modi’s India, the “world’s largest democracy”, is another big disappointment, as is Egypt. These derelictions will not be forgotten, and may affect future ties.

V

Venezuela’s hard-left government has been in America’s bad books for years. But when US officials visited recently to discuss resumed oil supplies in return for an easing of sanctions, they found a receptive audience. In contrast, when Joe Biden phoned the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman (a keen Putin fan), requesting increased oil production to compensate for banned Russian exports, he refused to take the president’s call. US-Saudi relations have been in the toilet since Jamal Khashoggi’s 2018 murder. This incident will make matters worse.

W

War crimes investigators face a big test as evidence mounts of multiple atrocities by Russian forces – exemplified by last week’s Mariupol maternity hospital bombing. “Universal jurisdiction” prosecutions are contemplated in national courts. And the international criminal court has begun investigations. But like the US and China, Russia does not recognise the ICC’s authority. This situation must change if war crimes are to be justly punished, now and in the future.

X

Xinjiang, home to China’s persecuted Uyghur Muslim minority, is one of many global troublespots whose urgent problems have been eclipsed by Ukraine. Millions of Afghans enduring a winter of hunger and fear under Taliban rule suddenly seem forgotten. The plight of civilians caught up in Ethiopia’s civil war is another glaring blindspot.

Y

Younger generations the world over have reason to wonder what’s going on. First they inherited the climate crisis, then came the pandemic, and then the resultant bans on study and travel. Now they face something older generations said would never happen again: a full-scale war in Europe.

Z

“Z” is a fascist-style pro-war motif displayed by Russian invasion forces and rightwing Putin supporters. But the “Z” that will be remembered with admiration around the world belongs to the name of Volodymyr Zelenskiy Ukraine’s comedian president turned inspirational war leader, who embodies the fight for freedom.

I write from Ukraine, where I’ve spent much of the past six months, reporting on the build-up to the conflict and the grim reality of war. It has been the most intense time of my 30-year career. In December I visited the trenches outside Donetsk with the Ukrainian army; in January I went to Mariupol and drove along the coast to Crimea; on 24 February I was with other colleagues in the Ukrainian capital as the first Russian bombs fell.

This is the biggest war in Europe since 1945. It is, for Ukrainians, an existential struggle against a new but familiar Russian imperialism. Our team of reporters and editors intend to cover this war for as long as it lasts, however expensive that may prove to be. We are committed to telling the human stories of those caught up in war, as well as the international dimension. But we can’t do this without the support of Guardian readers. It is your passion, engagement and financial contributions which underpin our independent journalism and make it possible for us to report from places like Ukraine.

If you are able to help with a monthly or single contribution it will boost our resources and enhance our ability to report the truth about what is happening in this terrible conflict.

Thank you.

Luke Harding

Foreign correspondent