by GRAIN | 29 Sep 2020 Corporations

The Silverlands Fund’s business model is all about bringing industrial agriculture to Africa. (Credit: Oaklins)

Financial flows going into agriculture are growing more and more institutionalised – and more and more private. To be sure, investing in agriculture has been going on since time immemorial. After all, farmers do it every day as they improve their soils, set up cooperatives, share knowledge with their children and develop local markets. But since the mid 2000s, institutional investment in agriculture has started growing. From seven agriculture-focused funds in 2004 to more than 300 today, the interest in capturing profits from farming and agribusiness on a global scale is real – and Covid-19 is not slowing things down. Who is involved? Where is the money going? How do these funds pay off for the financial players and for local communities? These are some of the questions we set out to get answers to, in order to better understand capital flows and who is influencing the direction of agriculture today.

Before the global financial crisis erupted in 2008, there was just a handful of funds catering to investors wanting to get involved in farmland and food production. Valoral, an investment advisor in Argentina, counted seven such funds in 2004.1 GRAIN identified 55 a few years later.2 Today, according to Preqin, a London-based alternative investment intelligence group, there are more than 300.3

Most of these funds are “private equity” funds. That is, they are pools of money injected into private companies that are not listed on stock exchanges (and therefore not subject to public reporting requirements). Private equity funds are managed by small, specialised teams and tend to attract a very specific kind of clientele. As they normally require minimum investments in the millions of dollars, which then get locked up for five to 15 years, this kind of investing is only accessible to pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowment funds, family offices, governments, banks, insurance companies and high net worth individuals. This will be changing soon, as the US opens the door for private equity firms to tap into the retirement savings of individual workers, but for now it’s only these big institutions which are involved.4

Private equity investing bloomed in the 1980s when “leveraged buyouts” and “venture capital” became well known strategies to take over companies and buy into startups. Investment houses like KKR, Carlyle Group and Bain Capital grew legendary on Wall Street and notorious on Main Street for their hyperbolic projects, cut throat methods and fantastic profits.

Private equity investing bloomed in the 1980s when “leveraged buyouts” and “venture capital” became well known strategies to take over companies and buy into startups. Investment houses like KKR, Carlyle Group and Bain Capital grew legendary on Wall Street and notorious on Main Street for their hyperbolic projects, cut throat methods and fantastic profits.Today, the private equity industry has secured a solid spot on the investment landscape. In 2019, it ranked third among institutional investing spaces, with over US$4 trillion under management (see table 1). This is comparable to the US$4.5 trillion wielded by the world’s development banks, and far outstrips the US$1.5 trillion invested by US and European philanthropic foundations.5

Table 1: Institutional investing (assets under management, 2019)

|

|

USD

|

|

Pension funds

|

40 trillion

|

|

Sovereign wealth funds

|

8 trillion

|

|

Private equity funds

|

4 trillion

|

|

Hedge funds

|

3 trillion

|

Source: compiled by GRAIN, figures rounded

But the reality of private equity investing is not as glossy as Wall Street spin would make it out to be. GRAIN took a look into how it’s operating in the field of food and agriculture today and came out with some important findings.

The big picture

Information about private equity is not easy to come by, as private equity firms are not required to publish data about their operations.6 But we were able to access some specialised data to get a look at the industry’s footprint in food and agriculture. The data is incomplete, but it does give some clear indicators (see box: A word on the data).

A word on the data

In early 2020, GRAIN studied over 300 funds active in the area of food and agriculture. Our departure point was a list of funds focused specifically on “natural resources” according to Preqin, the industry leader in data on “alternative” investments (anything not stocks or bonds). “Natural resources” covers energy, timber land and farmland. From this group, we screened out those funds specifically investing in agriculture. We added to this a number of funds classified as broader “private equity” funds which appeared on our radar because of significant deals they made in the agriculture arena. But we did not screen the full set of generalist private equity funds as there are 3,500 of them. Nor did we comb through the nearly 4,000 buyout deals or the 3,700 venture capital deals tagged “food” or “agribusiness” by Preqin.

This means that we stayed close to the production process – farming, livestock production and fishing. It also means that our dataset is not comprehensive. It is, however, representative of private capital investing in agriculture, as our findings align with Preqin’s overall reporting.

While our main source of data was the Preqin Pro database, publications and staff, we also relied on AgriInvestor, Pensions & Investments, company websites and generalist news sources like the Financial Times.

Scale and scope of ag investing

Today, at least 300 private equity funds are specifically oriented towards food and agriculture.7 A subset of these, run by 200 fund managers, are focused on farmland per se (acquiring or operating farms). Other private equity funds, with diversified portfolios, also buy into food and agriculture, but usually on the downstream side (processing, distribution and service). Preqin’s assessment of farmland funds shows a rising number of closings over the years, peaking in 2013 and again in 2019 (see table 2), with a total aggregate capital raised of US$8.4 billion in 2019.

Table 2: Annual unlisted agriculture/farmland fundraising, 2008-2019

|

Year of final close

|

No. of funds closed

|

|

2008

|

5

|

|

2009

|

5

|

|

2010

|

9

|

|

2011

|

14

|

|

2012

|

13

|

|

2013

|

20

|

|

2014

|

17

|

|

2015

|

11

|

|

2016

|

13

|

|

2017

|

11

|

|

2018

|

17

|

|

2019

|

21

|

Source: Preqin Ltd8

The dataset we studied, mixing funds and fund managers active in both farmland and agriculture, accounted for nearly US$300 billion (not exclusively dedicated to agriculture). In terms of geographical focus, most the of the agricultural investments targetted Africa (56 funds accounting for US$105 billion) followed by North America (130 funds, US$104 billion), Asia (111 funds, US$41 billion), Europe (30 funds, US$24 billion), Latin America (59 funds, US$16 billion) and West Asia / North Africa (18 funds, US$3 billion). What this tells us is that agricultural investing through private equity is quite active across the global South, with much of the funds landing in Africa.

“They bought everywhere … orchards and vineyards. They offered a low price, around US$500-US$600 per hectare,” says a land agent in the Moldovan village of Văleni about NCH Capital. “People, if left alone, old, without help, without support, they have no choice but to sell — and many sold.” (Screenshot from “NCH: The agribusiness success story”, Vimeo)

Who is involved and who benefits?

As mentioned earlier, these funds draw capital from institutional investors (see box: How does private equity work?). Workers may despise private equity firms for their brutal buyout practices, but nearly half the money engaged in private equity as a whole (46%), and agriculture and farmland investing specifically (44%), comes from worker pension funds. Most pension funds tied up in agriculture have their headquarters in North America and Europe, with the remainder spread across an assortment of countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America.9 Many of the pension funds investing in agriculture or farmland are not yet at their target allocation level for this asset class, which tends to be around 4-5%, which means they still aim to invest further. Whether these funds serve public or private sector retirees, the fact is that nearly half the money going into agricultural investing through private equity is workers’ retirement savings – whether they are aware of it or not and whether their interests are well represented through these investments or not. This points to a potentially huge accountability gap, as there is a lack of transparency around these investments. But it also underscores the frightening fact that pension savings are the biggest pot of money “out there” and they are not necessarily being managed in the interest of workers or the local communities where capital is being deployed.

Another major player are the development finance institutions (DFIs) run by governments.10 DFIs are quasi public bodies that operate on a for-profit basis, often alongside development cooperation offices. DFIs invest, rather than dish out grants. And they are quite active in agriculture, a long standing target area of foreign aid. It is often said that when DFIs subscribe to a private equity fund this is taken as a “stamp of approval” that enables other sources of capital to join in. In Africa, DFIs are particularly critical to private equity funds, even more so than pension funds. This means that DFIs carry a serious amount of responsibility for how private equity investing in agriculture pans out, at least in Africa.

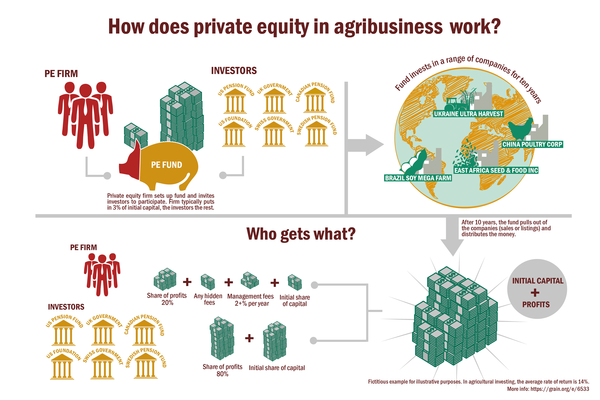

How does private equity work?

Private equity is organised differently in the US and Europe, with firms in other regions using one or the other setup. But there is a similar pattern.

A small team of experts (a “private equity firm” led by “fund managers” in Europe – or a “limited liability company” led by “general partners” in the US) will design a fund with a view to investing in a certain area. The fund will have a particular theme and strategy to it (e.g. early stage funding for small- and medium-sized enterprises in Africa) and it will normally be registered in a tax haven like Cayman Islands, Mauritius, London or Delaware. The experts will then go fundraising and secure commitments (also called “subscriptions”) from a number of investors, be they development banks, foundations or pension funds. Once the pool of money is committed, the fund “closes” and the managers get to work looking for where to invest the money. The investments can take various forms. They may be venture capital deals (money going into young, startup companies), growth investments (for instance, helping a company go international) or buyouts (leveraged or not, taking a majority of shares or not), to name a few types. A fund will normally end up with a “portfolio” of several companies it invests in, or properties in the case of farmland. Fund managers often play an active role in those companies, from chairing the Board to implementing strategic changes.

Typically, a private equity fund has a life span of no more than 10 years, meaning that all the investments made by the fund must be liquidated (i.e. “exited”) within that time, either by selling out of the companies and assets the fund has acquired or taking the companies public by listing them on a stock exchange. At that point, the investors will recuperate the capital invested plus their share of any profits, minus the fees paid to the fund managers. The fund may also generate losses, resulting in the investors losing some or all of the money they invested.

Returns for whom?

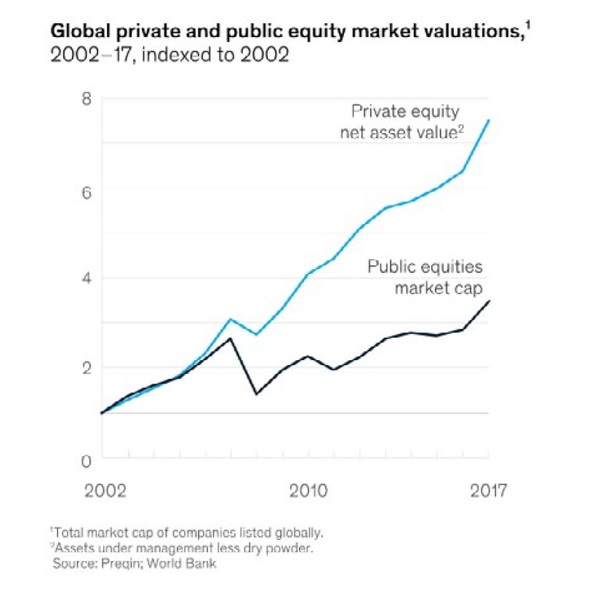

Private equity funds invested in food and agriculture normally pay out annual “management fees” of 2% on the total capital invested to fund managers, whether the investment succeeds or not. The fund managers also typically take 20% of the profits generated by the fund, either deal by deal or at the end of the fund’s lifespan. Given that the fund’s managers, or general partners, normally only put in 1-5% of an investment, the payoff for them, in terms of risk, is very high (see illustration). Added to this are quite a number of hidden fees that may be charged to funds or to individual deals, whether legally or not, as well as tax loopholes.11 The general partners may, for instance, receive fees for sitting on the boards of the various companies the fund has taken shares in or charge these companies service fees.12 Since a notable share of the world’s wealthiest are connected to private equity, it’s reasonable to deduce that the managers, or general partners, do quite well.13 But for those who invest, the limited partners, it’s another story. From the data we saw on farmland and agricultural investing, funds differ on returns for investors. Some lose money, many hover around 8-12% per year, some go as high as 40%. By our calculations, the average net internal rate of return (i.e. the annualised return on investment minus fees) for funds investing in agriculture in 2019, by region where the investment goes and just for those cases where data is reported, was 14% in Africa, 12% in Asia, 11.6% in Latin America and 9.9% in North America. (For Europe and West Asia / North Africa there is not enough data.) By comparison, median annualised net returns for private equity as a whole for the last three years is said to be 17%.14

But these industry-reported figures are contested. Right now, there is a big debate about whether or to what extent investors like pension funds have been “enticed” to go in private equity based on inflated promises, as the returns are not much higher than had they invested in public equity markets. Independent research looking at the period 2006-2019 finds the returns are more like 11%.15 Calpers, one of the US’ biggest public pension funds, openly states now that their returns, net of fees, have been 10.7% per year. This could be considered comparable to having invested in the stock market through an index fund except it leaves out the fees that Calpers and all other private equity investors paid to the fund managers over the same period, which adds up to a whopping US$230 billion. This is a huge transfer of capital straight into the pockets of a small group of funder managers.16

“Before, we planted rice, beans, maize, pumpkin. But not now. The space is too little because of the farms; we’re surrounded,” says Maria de Lurdes Gomes, a mother of 12 children who is part of a Quilombola community living in the area of Tocantins, where Pátria is buying farmland. (Credit: Folha de Sao Paolo)

Contrast this with how these investments pan out for communities on the ground. For many, just the term “private equity” strikes fear because so many deals have led to workers in the target firms being laid off, management teams replaced, the companies stripped of equity and filled with debt, and eventually crippled and shut down. Many examples of this abound in the US, a recent example being the destruction of Toys ‘R Us and its 33,000 jobs.17 But they also occur in other places like India, as we see with Omnivore Partners in the annex to this report.

Ethics, transparency and regulation

The private equity industry is subject to very little regulation or oversight, which is a central part of its appeal to investors (and why it is often anchored offshore). In 2010, the US passed legislation requiring private equity firms managing more than US$150 million to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission, but the SEC has done little to exercise oversight on these companies.18 In Europe, the EU has also tried to move toward more disclosure and oversight, without rocking the boat, while the UK has promised that Brexit would deliver less regulation.19 Kenya has no overarching regulation of private equity, while Brazil, India and other countries do not have strong controls either.20 Apart from lax requirements on reporting and disclosure, excessively aloof tax treatment is a huge issue. Fees tapped by investment managers are taxed as income, but profits are taxed at a much lower rate as capital gains. This creates an incentive for managers to forego “fees” and take them as profit payouts. In addition, many payments reportedly go unrecorded and untaxed, and the structure of most funds, which run through multiple subsidiaries in offshore tax havens, can facilitate transfer pricing or tax evasion, as is alleged in the case of NCH Capital’s activities in the Ukraine discussed in the annex to this report. Even when authorities catch up with the companies, they tend to settle the matter for an agreed amount without changing rules or practices.21

When it comes to political or societal accountability, there is next to none. The industry likes to present its slow adoption of “environment, social and governance” (ESG) credentials and signature of texts like the Principles for Responsible Investing as proof of good conduct. But, as can be clearly seen with their investments in farmland, this is superficial and self-serving.22

Are workers checking up on their pension fund managers?

GRAIN has been pointing to the role of pension funds in land grabbing for agricultural production on a global scale since 2011.23 We have even exposed powerful findings and allegations surrounding the operations of TIAA, the largest pension fund in the US, which has adopted farmland investing as a unique strategy and drawn numerous other pension funds into its investments, in Brazil.24 TIAA has now spun off an entire division, called Nuveen, to manage its farmland portfolio which also spans Europe, Australia and the US. Nuveen is today the world’s single largest farmland investor.

In researching this paper, we were surprised to learn that in 2017, the United Auto Workers (UAW) Retirees Medical Care Trust had US$400 million invested in farmland deals in Brazil through Proterra, Black River and Amerra.25 UAW is a major US labour union and the Medical Care Trust is managing the health care benefits of its pensioners. Proterra and Black River are private equity firms dedicated to farmland buyouts that were spun-off from Cargill.26 Right now, Proterra has a whopping US$3 billion under management, including $600 million in “dry powder” (funds committed by investors, but not yet invested anywhere). One fund they manage with UAW money is the Black River Agriculture Co-Invest Fund A, which takes controlling positions in farms in Australia and Latin America, for a net return of 14.1%.27 Amerra, for its part, is a private debt and equity investor focused on agriculture, with US$1.8 billion under management. Amerra has a less than stellar reputation. The firm, know for running after distressed assets, a strategy called “vulture investing”, is being sued by several major banks for aiding and abetting fraud committed by the international cocoa trader Transmar.28 It has also recently seen its bids for Brazilian agribusiness assets shot down and been taken to court for other matters.29 UAW’s farmland holdings may have changed since 2017, but the question remains whether and to what extent its workers are aware of and exercise oversight over how their funds are managed.30

In July 2020, the International Union of Food, Agricultural, Hotel, Restaurant, Catering, Tobacco and Allied Workers’ Associations released a commentary in relation to the US government’s clarification that the private equity industry may now get access to individual retirement savings. They urge that labour organisations “push for public investment vehicles, backed by central bank guarantees, to support sustainable jobs and the transition to a low-carbon economy, and cut the umbilical cord linking workers’ futures to junk bond billionaires.” Given the deep “umbilical” connection between private equity, farmland grabs and the food system, this call could not be more urgent.

Private equity, public problem

Private equity is only one class of investors taking control of assets in the food and agriculture sphere – from farmland to grain terminals to meat processing plants to food delivery – and transforming realities for farmers, fishers and workers. But it is a powerful class. Though its operations are opaque and barely accounted for, private equity as a sector has grown enormously since the 2008 financial crisis and is becoming more concentrated. It is also becoming increasingly present in the global South.31

This trend is part of broader process by which the world of finance – banks, funds, insurance companies and the like – is gaining control over the real economy, including forests, watersheds and rural people’s territories. This is called financialisation. Apart from uprooting communities and grabbing resources to entrench an industrial and export-oriented model of agriculture, it is shifting power to remote board rooms occupied by people with no connection to farming, much less local concerns, and who are merely in it to make money.

Local communities, tormented by the unbearable smell and constant presence of flies generated by the Coexca pig farm funded by Danish private equity in Chile, pushed on their local authorities to take action. (Credit: Resumen Chile)

It is disconcerting that the biggest players in the private equity industry are people’s pension funds, followed by governments’ development finance institutions. They are responsible, yet there is zero connection between them and the people whose money they are investing, much less between them and the communities impacted by these investments. As the examples in the next section show, this has to change, for they have too much power and too little accountability. With the world grappling with a Covid-triggered economic crisis and an escalating climate crisis, we have to put the question of how to better support people’s retirements, and how to dismantle not entrench the industrial food system, on the table. In the process, we might manage to eliminate private equity altogether.

Annex: Case studies of private equity in agribusiness from around the world

NCH Capital: Eastern Europe’s leading land baron

New York-based private equity firm NCH Capital was founded in 1993 by two US businessmen, George Rohr and Moris Tabacinic, active in the privatisation frenzy that followed the break-up of the Soviet Union. They saw a big opportunity in the area’s farmland and, beginning in 2005, established several funds with the idea of leasing or buying up farms for cheap and aggregating them into large-scale, US-style grain and soybean farms.

NCH drew in major investments from US and European pension funds, endowments and foundations, like the Harvard University Endowment Fund, the Dutch pension fund PGGM, and the foundation of eBay founder Jeff Skoll. It then channelled these investments through an opaque, offshore structure running from the Cayman Islands to Cyprus and into a “network of joint venture relationships” with local players to take over farmlands in the Ukraine, Russia and other former Soviet republics.32

NCH’s most important backer in this venture was the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Between 2009 and 2014, the EBRD provided NCH’s Cyprus-based holding companies with US$140 million in low-interest loans, and in May 2013 the EBRD took a direct US$100 million equity stake in one of NCH’s farmland funds.33

According to a Latvian company that was NCH’s main joint venture partner for its Ukrainian farming operations, NCH used the low interest loans provided by the EBRD to its Cyprus-based companies to lend onwards to its joint venture farming operations at higher interest rates.34,35 It also required these subsidiaries to purchase equipment and supplies from the offshore companies at inflated prices and to sell back grains and other products to these offshore companies at a discount. In cases that are now before the courts in Latvia and the Ukraine, NCH’s Latvian partner alleges the scheme siphoned profits out of the Ukraine joint ventures to the offshore entity, depleting their share in the profits and enabling NCH to evade taxes. Eventually, the Latvian partner says, NCH fraudulently pushed them out of the company and forced them to accept a buy-out for much less than what their shares were worth. Overall, they estimate that NCH’s actions cost them US$10 million in lost profits.36

Today NCH claims to have amassed a land bank of 700,000 hectares in Russia and the Ukraine, with other holdings in Romania, Moldova, Kazakhstan, Latvia and Bulgaria.37 It is unclear how NCH was able to skirt the various restrictions on foreign farmland ownership that exist in many of these countries. In Moldova, investigations by RISE Moldova found that NCH was able to exploit a loophole in the country’s prohibition on foreign farmland ownership by hiding purchases of farmland through a Moldovan company that is in fact owned by another Moldovan-registered company entirely owned by one of NCH’s Cyprus-based holding companies.38 This Moldovan company amassed huge areas of farmland for NCH by targeting elderly farmers, vulnerable to selling their lands for cheap.

“They bought everywhere … orchards and vineyards. They offered a low price, around US$500-US$600 per hectare,” says Gheorghe Severin, a land agent from the Moldovan village of Văleni. “People, if left alone, old, without help, without support, they have no choice but to sell and many sold.”39

In the Ukraine, NCH has had to lease lands from small farmers because of a moratorium on the sale of farmland. But this is changing. After years of pressure from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the EBRD, the Ukrainian parliament was finally arm-twisted, via an IMF Covid relief package, into passing a hugely unpopular land reform bill that lifts the moratorium and could eventually open the door for foreign companies to acquire Ukrainian farmland.40 NCH was an active participant in this orchestrated coup. It was a visit to the Ukrainian President by the US Secretary of Commerce in 2015 that really set the ball in motion for the changes to the land law. The US got an agreement from the Ukraine during that visit that it would implement an IMF reform plan, which included the privatisation of land, as a condition for two US$1 billion loan guarantees from the US government.41 One of the few business delegates joining the US Secretary of Commerce for these high-level meetings was none other than NCH founder and CEO, George Rohr.42

Tiga Pilar Sejahtera Foods, a major noodle producer part owned by private equity giant KKR, has 60,000 hectares of oil palm plantations in Indonesia. (Credit: GA Photo/Mohammad Defrizal)

KKR: barbarians at the barn

Kolberg Kravis Roberts, the Wall Street firm that invented the leveraged buyout in the 1980s and became immortalised in the book “Barbarians at the gate”, is one of the world’s biggest private equity groups. (The top four are known as “ABCK” for Apollo, Bain, Carlyle and KKR.) It has concluded some 42 deals in the food and agriculture arena for US$61 billion. Some of these deals have been significant.

-

In 1987, in the US, KKR bought out RJR Nabisco for US$25 billion, took it private, dismembered it and sold off its parts like Del Monte Foods, Chun King and Babe Ruth/Butterfinger, before finally exiting in 2005. They also bought into and exited other major US food corporations like Beatrice Foods.

-

In 2014, KKR bought into Afriflora Sher, a major global rose producer registered in the Netherlands but with its farms in Ethiopia, for US$200 million. “We see Africa as a long-term attractive investment destination… the potential is astounding,” KKR’s Head of African operations Kayode Akinola gushed at the time.43 Equally enthusiastic, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation loaned the farm another €90 million the following year. By the end of 2017, KKR announced it was pulling out of Sher and dissolved its African investment team as it “couldn’t find enough big companies to buy”.44 Despite Akinola’s earlier enthusiasm, that was their one and only direct investment in Africa.

-

In Indonesia, since 2014, KKR has amassed a significant share of Tiga Pilar Sejahtera Foods (20% of assets, 35% of voting power) and Japfa Comfeed (currently 8% of assets, down from 12% in 2019). Both are leading corporations in the country’s poultry, rice, noodles and palm oil markets. In fact, Japfa is the second largest poultry operator in Indonesia, with 100 company-owned farms and 9,000 contract producers.

-

In China, KKR bought up 70% of COFCO Meat before taking it public, 24% of China Modern Dairy Holdings before selling it to China Mengniu, a share of Ma Anshan Modern Farming, now one of China’s largest dairy farming companies owned by Mengniu, and an 18% share of chicken producer Fujian Sunner Devt Co, the top poultry supplier for China’s fast food industry (KFC, McDonalds). Most of these transactions took place between 2014 and 2017, showing the powerful appetite of KKR for top tier agribusiness corporations. As a private equity firm, its objective is not to stay long in any of these companies but to move in, restructure the firm and then pull out a few years later for a significant profit.

-

The KKR Asian Fund III, a US$8.5 billion buyout fund which has recently invested in various food companies, including Unilever Indonesia’s spreads business and Arnott’s Biscuits in Australia, is clocking net annual returns for its investors – mainly pension funds and insurance companies – of 23.7%, down from 43.3% last year.45

The Wall Street giant has chalked up some notable fails, too. It tried to take over Spain’s Pescanova, one of the largest fishing companies in the world, when it was going bankrupt in 2013. The same occurred with Birds Eye, the UK’s top frozen fish company, when Unilever put it up for sale in 2006. Neither deal pushed through.

It is worth noting that KKR is, directly or indirectly, invested in farmlands though its holdings of Tiga Pilar Sejahtera Foods (60,000 ha of oil palm plantations) and Japfa in Indonesia (100 poultry farms, hectarage unknown), Fujian Sunner Development Company (300 poultry farms, hectarage unknown) in China and Sundrop (20 hectares of greenhouses) in Australia. It is also worth noting that COFCO Meat, Japfa, Modern Dairy and Sunner score as “high risk” companies on the FAIRR ranking of protein producers, meaning they are among the worst performers in terms of sustainability.46

In May 2020, KKR announced it was taking its Asian Fund III even further and investing US$1.5 billion through it in Reliance Jio, the Indian telecommunications giant run by Asia’s top billionaire Mukesh Ambani. This gives KKR a 2.3% stake in the company, along with Facebook (10%) and a few other new entrants. As Facebook owns Whatsapp, one of the most powerful consumer platforms in India, Reliance Jio could become a key logistics and payment hub for food retail and delivery in India, potentially taking over the informal sector.

Carlyle’s agribusiness ventures

Similar to KKR is The Carlyle Group, one of the world’s biggest, highly diversified private equity companies. Through various funds, as well as direct investments, it has stuck its teeth into agriculture and agribusiness across the global South.

In 2012, through its maiden Africa fund, Carlyle bought into the Export Trading Group, a major commodity trader of African agricultural products, for US$210 million. Co-investors were Remgro and Afirma Capital. In 2015, Carlyle sold its stake back to management for an unknown amount. (Following this, Japan’s Mitsui acquired 30% of ETG for US$265 million.) In 2018, Carlyle bought out South Africa’s Tessara, a food packaging manufacturer.

In Asia, Carlyle has been far more present and active. In 2011, it directly tried to buy a US$200 million stake in Garuda Food, one of Indonesia’s top food conglomerates, but failed. In 2017, together with Citic Ltd, it bought an 80% stake in McDonald’s China. In 2018, it tried to buy the consumer foods division of Kraft Heinz India but walked away. And right now it is bidding for Sunrise, an India-based international producer of spices, oil and papad.

Between 2009 and 2010, Carlyle took minority stakes in the Chinese dairy company Yashili, China Agritech and China Fishery Group. (In 2013, China Fishery Group bought out Peru’s fishmeal producer Copeinca.) In India, Carlyle bought out one of the country’s lead dairy producers Tirumala Milk Products in 2010 for $23.3 million, which four years later it sold to the French dairy giant Lactalis.

In Saudi Arabia, Carlyle bought a 42% share of the Al Jammaz Group in 2011. Al Jammaz owns Alamar, the franchise operator of various fast food chains in the region (Dominos Pizza, Wendy’s, Dunkin Donuts). But it is also involved in marketing agricultural inputs (seeds, crop chemicals, irrigation, machinery, animal health products and feed additives) plus date farming in Saudi Arabia. In 2013, Carlyle bought a minority stake in Nabil, a meat manufacturer based in Jordan.

These investments were done on behalf of Carlyle clients, mostly US and European pension funds, foundations and insurance companies.

Helios Investment Partners: a big player in Africa

Helios Investment Partners has long claimed to be the largest Africa-focused private investment firm. The size of its funds would appear to support these claims. Its latest two funds, which devote a significant portion to food and agriculture, raised over US$1 billion each. Yet, as with most African-focused private equity funds, Helios has received a big part of its capital from development banks like the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) of the US or the UK’s CDC Group, which recently pumped US$100 million into the Helios Investors IV fund.47 In the words of Henry Obi, the firm’s Chief Operating Officer, “Helios would not be standing here today without OPIC. They gave us our first break in 2004 and now we manage more than $2 billion, investing in all sorts of projects across Africa.”48

Helios’ two biggest plays in African agribusiness were the acquisition of Louis Dreyfus’ West African fertiliser business and the takeover of West Asia and North Africa’s largest hybrid seed company. In both instance, Helios partnered with other investors. The fertiliser business was purchased with Temasek, the investor for Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund. The French commodity trader Louis Dreyfus had done little to invest in this sprawling company, once known as SCPA Sivex International, since it acquired it for US$85 million from the French state under a privatisation process in 2011.49 But just six years later, the Financial Times reported that Louis Dreyfus sold it to Helios and Temasek for US$200 million.50 The new owners have given the company a makeover and a new name (Solevo) and are keen to associate themselves with the rice self-sufficiency campaign of the government of Côte d’Ivoire.51

The seed company Helios acquired, Misr Hytech, was previously the Egyptian subsidiary of the Proagro Group of hybrid seed companies, which has its headquarters in the US but operates mainly in West Asia, North Africa and India. In this case, the deal was initiated by another private equity group, Lorax Capital Partners – an Egyptian company formed to administer the Egyptian American Enterprise Fund that was established during the Obama administration “to promote policies and practices conducive to strengthening the private sector in Egypt” in the wake of the overthrow of the US’s long time ally Hosni Mubarak. The US Congress created this fund to “empower Egyptian entrepreneurs” and to invest “particularly in small- and medium-sized enterprises”.52 Strange, then, that it would partner with a UK-based private equity firm to take over a US-owned company that is said to be the largest hybrid seed producer in the Middle East.

In July 2020, the Canadian private equity group Fairfax, a unit of the Ontario government’s pension fund, merged with Helios.53 The new entity has a combined US$3.6 billion under management, with Helios holding 45.9% of the shares. Previous Helios funds and investors will now shift to the new company which aims to become a bigger and more diversified player in the African landscape.

SilverStreet Capital: investing in African farms, profiting in European tax havens

The story goes that Gary Vaughan-Smith came up with the idea of setting up a private equity fund to buy farmland in Africa while working at a Dutch asset management company during the food and financial crisis of 2007-8. Witnessing how pension funds were running scared for “real assets” that could insulate them from a collapsing stock market, Vaughan-Smith, who grew up in Zimbabwe, saw an opportunity in the fertile and cheap farmlands of southern Africa. “I find it really exciting to be able to bring this sort of investment capital to Africa,” Vaughan-Smith told one pension fund investor magazine.54

The private equity firm that Vaughan-Smith would form to lead this venture, SilverStreet Capital, was set up in the UK. Its maiden fund, Silverlands Fund, closed in 2012 with US$214 million, almost half of this coming from Danish pension funds.55 The rest was supplied by development banks, like the CDC Group of the UK, OPIC of the US, FinnFund of Finland and the IFU of Denmark. OPIC and the World Bank’s MIGA also chipped in with political risk insurance to cover the fund’s investments.

The fund’s business model is pretty simple. It aims to bring Western industrial agribusiness to Africa by running its own large-scale farms, organising contract production with local farmers and selling hybrid seeds and chicks to farms in countries like Zambia and Tanzania. It does this through numerous subsidiaries, most of which are fully owned by the fund. With so many development banks on board, SilverStreet is highly sensitive to accusations of land grabs and each year it publishes “impact and ESG” reports that are full of examples of how the fund is benefiting Africans.

But one can question how much of the capital “invested” in Silverlands is truly making it to the African continent and staying there. The investors who signed up to the Silverlands Fund, registered in the tax haven of Luxembourg, agreed to pay Vaughan-Smith’s firm an annual 2% management fee on the total commitments to the fund, or roughly US$4-5 million every year.56 This means that over the fund’s lifespan of 10 years, the fund managers will take US$40-50 million from the total pot, allegedly to pay overhead costs, due diligence expenses and monitoring. The African portfolio companies may be a source of additional fees for the fund managers. For instance, the Silverlands Fund is invested in a South African-based company for which Vaughan-Smith sits on the board. In 2019, that company paid him personally over US$14,000 in fees, while another SilverStreet manager who also sits on the board received nearly US$17,000.57

It is difficult to asses how much Vaughan-Smith and his partners make from such fees because the operations are run through numerous companies, most of them offshore. The management fee payouts, for instance, go to the Luxembourg company SilverStreet Management, which is the general partner of the Silverlands Fund. It then pays “advisory fees” to two other companies: one called SilverStreet Capital Agricultural Advisors for which there is no public information because it is based in the opaque tax haven of Guernsey and another called SilverStreet Capital LLP, which is based in London. This latter company is at least 75% owned by Vaughan-Smith, and also lists his wife as a director.58

The Silverlands Fund targeted a net internal rate of return in the mid-teens, according to a recent company presentation.59 With 17% of the profits going to Vaughan-Smith’s firm as a performance fee, and without having put more than a few thousand dollars of their own in the fund’s starting capital, the general partners stand to walk away with perhaps US$100 million or more.60 By contrast, the firm says it increased farmers’ incomes on average by about US$330 per year.61

Bill Gates: private equity to fight poverty?

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is one of the biggest philanthropies bankrolling the spread of the industrial agriculture model in the global South. They are a lead contributor to the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, and largely underwrite the quasi-public international agricultural research system. Through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Trust, which manages the foundation’s endowment, the couple are also invested in private equity, taking positions in farm and food businesses around the world.62

In Asia, Gates is invested in Stellapps, an Indian start-up that is digitising the country’s massive dairy industry. The company presently works with five million local dairy farmers offering them software and internet related services. In 2018, Gates contributed to a US$14 million round of funding for Stellapps, its first ever equity investment in Indian agriculture.63 Earlier, over in China, Gates was involved in Hony Capital Fund III, which conducted two buyout deals in Beijing’s bustling supermarket sector. In 2009, the fund took a 25% share of the Beijing Merry Mart food store chain for $117 million and an 11% stake in the city’s Wumart Stores chain for $213 million.64

In Africa, Gates participated in a fund managed by the Dubai-headquartered Abraaj Group, a US$14 billion private equity “trailblazer” that collapsed in 2018 under a blanket of debt and allegations of fraud. In 2009, Abraaj’s US$105 million Health in Africa Fund took a 49% stake in Gallus, a poultry rearing operation in Tunisia, from which it exited five years later.65 In 2009, the fund also paid US$18.7 million for a 10% stake in Brookside Dairy in Kenya.66 Brookside is a dairy processing company set up by the country’s powerful Kenyatta family, which retained the other 90%. It controls 45% of the Kenyan packaged milk market and exports to Tanzania and Uganda. In 2014, French dairy giant Danone bought a 40% stake in the company, which at the time was harbouring plans to expand. (For instance, in 2016, Brookside took over Inyange, Rwanda’s top food processing company connected to President Paul Kagame’s party.67) Today, Brookside is the largest dairy processor in East Africa, buying milk daily from 200,000 farmers and operating in 12 countries. In 2017, before it collapsed, Abraaj’s fund also invested in Sonnendal Dairies (Pty) Ltd in South Africa.

The Gates Foundation Trust is also invested in several funds managed by Kuramo Capital Management, a New York-based investment manager which in 2017 sank US$17.5 million into Feronia, the controversial oil palm plantation company in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In fact, as of July 2020, Kuramo has now gone on to take over Feronia. While it is not known if Gates’ money is directly tied to this purchase, the foundation maintains a strong relation with the firm. It most recently committed to the Kuramo Africa Opportunity Co-Investment Vehicle III, a separate account managed by Kuramo targetting natural resources investments in sub-Saharan Africa.68

Omnivore Partners: accountability gaps in India

How much are investors and private equity firms responsible when things go wrong? Ask that to the dairy suppliers and local employees of Doodhwala in Bengaluru, India.

Omnivore Partners is an Indian venture capital group that funds start-ups across India, especially in the food and agriculture space. They define themselves as “a ‘financial first’ impact investor, seeking to deliver market-rate venture capital returns, while impacting the lives of Indian smallholder farmers and rural communities.”69 In 2018, they set up a fund called Omnivore Partners Fund 2 which closed at US$100 million. Participants in the fund include European development banks (Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland and UK), affiliates of the insurance giant AXA and the agrochemical leader BASF, and even the Rockefeller Foundation. The fund invested US$2.2 million right away in a company called Doodhwala, the Hindi term for “milk deliverer”.

Doodhwala is a Bangaluru-based outfit created in 2015 to “disrupt” the dairy market by facilitating home delivery of fresh milk through a mobile subscription platform. Consumers would pay a subscription through their phone and Doodhwala would facilitate point to point delivery. By 2018, the company was delivering 30,000 litres of milk daily in three major cities (Bangalore, Hyderabad and Pune) and expected to reach 10 million subscribers by 2021.70

In 2019, however, the entire operation went bust. At first, the company fell behind on its payments to suppliers and employees. Then it cut off the phone. Now the Doodhwala founders are nowhere to be found and lawsuits have been filed in court.

As a result of all this, more than 100 employees and 35 milk suppliers have not been paid, including Karnataka Milk Federation (US$128,000 lost), Erden Creamery (US$33,300 lost) and Akshay Kalpa (US$84,000 lost) in Bangalore alone.71 Customers also lost money and some people are calling it a scam. One supplier says that the fraud occurred when an Omnivore partner was placed on Doodhwala’s Board of Directors.72 And yet the investors in the Omnivore fund back in Europe and the US are looking at a 25% net return on their investment.73 Are they aware of how things panned out for the people Doodhwala made commitments to?

Pátria Investimentos/Blackstone: blazing an agribusiness trail through the Amazon

Pátria Investimentos is credited as having pioneered the private equity industry in Brazil. But it was just a small player until 2010, when US private equity behemoth Blackstone took a 40% stake in the company. Since then, the firm has launched several private equity funds and attracted billions of dollars in investments from Canadian, European and US institutional investors and development banks. Blackstone’s entry into the company also marked its move into agribusiness, with a focus on Brazil’s northeastern “agriculture frontier”.

In 2015, Pátria created the Pátria Brazilian Private Equity Fund III to finance the construction of a controversial shipping terminal in the state of Pará, designed to transport agricultural commodities from deep in the Amazon to the ports of the east coast.74 The terminal, which is the largest grain loading and transportation capacity in northern Brazil, is run by Hidrovias do Brasil, a logistics company in which Pátria, Blackstone, Temasek, the pension fund of Alberta, Canada, the World Bank’s IFC and the Brazilian national development bank (BNDEPar) are all invested.75 This terminal has been linked to aggressive deforestation of the Amazon for the expansion of agribusiness.76

In the south of Brazil, Hidrovias controls 30% of all river transport on the Paraguay-Paraná waterway.77 The waterway, pushed by the governments of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay since decades, is a complex system of commercial navigation serving the region’s extractivist industries, especially mining, soybean and wood pulp. Yet it has been denounced from the beginning for its tremendous environmental, social and economic consequences. Impacts include soil and coastal erosion, loss of tourism opportunities, decline of fish populations, displacement of people due to flooding, human trafficking, loss of biodiversity and invasion of foreign species.78

Lack of consideration for such impacts plus other irregularities have led to Brazilian courts suspending Hidrovias’ operating permits for three ports in 2016.79 In 2017, one of the silos in the Hidrovias grain port in the district of Miritituba, in Itaituba, gave way because its support base could not bear the weight, leading to another port suspension.80 Despite these and other setbacks, Hidrovias do Brasil reported a gross profit of over US$100 million in 2019, up 32% from 2018, and its investors plan to take it public in 2020.81,82

Once it got involved in Hidrovias, Pátria went on an agribusiness shopping spree, buying up several of the remaining independent seed, fertiliser and pesticide dealers in the northeast of Brazil.83 Farmland was next on the agenda. “We saw that we were active across different points in the value chain, namely fertilisers and waterways, and we thought that there would be a lot of synergies as far as information flow and the activity of buying and selling farmland,” says the head of Pátria’s agribusiness portfolio, Antonio Wever.84

Pátria has so far launched at least two farmland funds focused on buying farmland in Brazil’s northeastern “agriculture frontier”.85 Its interest is in medium-sized farms of no more than 5,000 hectares where the owners are in financial difficulty or where there is a “transformation play” to bring pasture lands into crop production.86 Pátria does not publish information about its farmland funds and we were only able to identify two properties that they have acquired: one in the western part of the state of Bahia and the other across the border in Tocantins, where there are serious land conflicts between the communities that have traditionally occupied the lands and the large-scale farmers that have recently moved in.87 Most recently, in August 2020, Pátria acquired three citrus and cereals farms covering 1,700 hectares in the state of São Paulo, through its takeover of the Brazilian agribusiness services company Qualicitrus.88

As with most private equity operators, Pátria is not interested in staying long – just ten years. After that, it plans to sell to the biggest farmers in the area or to foreign companies. “We believe that, in the future, the restriction to foreign investors [to purchase land] will be altered. Maybe not in a year or two, but over the life of the fund this restriction is very likely to be changed, and then we would have the option of selling much larger packages of land to large international investors,” says Wever.89

With such big bets on the further opening of the Amazon and the Cerrado to agribusiness, it is not surprising that Pátria and Blackstone have been such ardent supports of Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro. After his election, Pátria assured their investors that Bolsonaro’s government was not a danger to democracy and that it would usher in “improved policies”.90 Blackstone, meanwhile, well known for its close connections to top US Republican Party leaders like Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell, was one of the main sponsors of a New York gala hosted in 2019 by the Brazilian-American Chamber of Commerce to celebrate Bolsonaro as its “Person of the Year” during his visit to the US.91

The favours run both ways. Bolsonaro’s government has made Hidrovias a partner for the privatisation and development of hundreds of miles of the national highway BR-163 that transports agricultural commodities from the Amazon to the southeast and that has recently been blocked by protestors of the indigenous Kayapó nation who say the road is spreading Covid-19 among their people.92 It appears that Bolsonaro also secured, during his visit to Riyadh in October 2019, a major investment from Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund in two of Pátria’s private equity funds.93

Denmark’s DFIs: private equity and pig farming in Chile

Coexca SA is a Chilean pork producer, processor and distributor created in the year 2002. It is now the second largest pork producer in the country, by number of slaughtered pigs, churning out more than 50 million kilos of meat per year.94

In 2017, the Danish Agribusiness Fund (DAF) decided to invest US$12 million in Coexca, the largest deal ever in the history of Chilean pork. The DAF is a fund run by a consortium involving the Danish government and a number of institutional Danish investors. It invests in the production, distribution and sales of food in the global South and it is managed by the Investment Fund for Developing Countries (IFU). The IFU is a government-owned private equity firm helping Danish companies invest in the global South, averaging a gross return of 12%. The DAF investment in Coexca was facilitated by an Edinburgh firm called JB Equity Limited, which planned to invest an additional US$40 million in Coexca over the next five years.95 “Our union with DAF and JB Equity will allow us to double Coexca’s current pork production capacity and establish a new and modern pig farm in the Maule Region of Chile,” Coexca CEO Guillermo García González said at the signing of the deal.96

In 2015, the company began construction of a 1,100 hectare pig farm called “Criadero San Agustín del Arbolillo”, designed to raise 10,000 sows per year in the commune of San Javier, province of Linares, Maule, Chile.

From the beginning, this farm has generated intense conflict with nearby communities, described by Chilean media as “a struggle of little people against giants.”97 The surrounding villagers organised a fierce resistance. They objected that the company did not have approval to use the lands where it was building its farm and that it was not complying with the legal obligations that were spelled out in the various permits it was granted related to change of land use, water works and changes in water courses, among others. They also raised concerns about the use of water, as the farm was expected to use five million litres of water per day, which is more than the amount used by the nearby city of San Javier. The villagers questioned why water rights would be authorised for such a highly polluting factory farm that would deplete their own water sources, leaving them dependent on limited water deliveries via municipal trucks.

Yet, in spite of these numerous concerns and the local resistance, the company, thanks to fresh financial backing from DAF and JB Equity, was able to move ahead with the construction of the farm in 2017.

Soon, the impacts were obvious. The local communities, tormented by the unbearable smell and constant presence of flies generated by the farm, pushed on their local authorities to take action. In October 2019, lawsuits were filed against Coexca for operating the San Javier pig farm without the proper environmental clearances and investigations began into the farm’s manure treatment system.98 The local mobilisation against the farm is the subject of a powerful documentary film called “Bad neighbour” that was released in 2019.99

In February 2020, the villagers finally won a ruling from the Court of Talca establishing that the company was violating the people’s right to live in an environment free of contamination in the town of San Javier.100 A few months later, on 10 June 2020, the Supreme Court unanimously confirmed the ruling of the Talca Court that accepted a claim filed by community members against the corporation for bad odours coming from the pig farm and partially accepted another claim filed by the National Institute of Human Rights against the Ministry of Health, the Superintendent of the Environment and Coexca SA.101

The Regional Chief of Maule, Nadia Gutiérrez, welcomed the Supreme Court’s ruling that Coexca has been violating the people’s right to live in a healthy environment, calling it “a triumph for the community of San Javier”.102 This means that the company must comply with environmental regulations. Is that too much to ask of a Danish government-led private equity project?

TLG Partners: investing in the wrong agricultural model in the Southern Cone

TLG Management Partners is a wholly-owned Uruguayan subsidiary of FJ Capital Partners, a UK-based private equity firm focused on agriculture, real estate and renewable energy.

TLG makes direct and indirect investments in “prime” farmland for a client base composed of European investment funds, family offices and high net worth individuals. Their portfolio includes 24 cattle and crop farms scattered across Paraguay, Uruguay and other parts of the Southern Cone of Latin America covering a total of 140,000 hectares.103

TLG has two cattle farms in the Paraguayan Chaco region that total 30,000 hectares. The farms, which are being managed on behalf of a European family office, became operational in September 2019.104 TLG says “Paraguay offers a refuge for investors” from the “instability affecting South America”. It points to the country’s low salaries and “triple 10” tax regime: 10% on corporate income, 10% on personal income and 10% on value added.105

TLG’s “refuge”, however, is also an environmental disaster. Cattle ranching is one of the main causes of deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco, which has an extremely fragile ecosystem that has already lost millions of hectares of forest. In 2017, the government itself projected that 400,000 hectares of forest would be lost each year over the next ten years from the expansion of cattle farms like TLG’s, as well as crop production.106 BASE-IS, a Paraguayan civil society organisation, reports that “in recent years, after deforesting a large part of the Eastern Region of Paraguay, the focus of activity has moved to the Chaco, where cattle ranching generates irreversible damage such as deforestation, desertification and salinisation of the soil, and threatens the cultural heritage and habitat of indigenous peoples, including one that has lived in voluntary isolation there for more than 2,500 years.”107

Similar issues are at play in neighbouring Uruguay, where TLG has eight farms covering 20,000 hectares of land dedicated primarily to the production of soybeans and rice.108 Soybean monoculture, in particular, is a leading threat to rural communities in Uruguay and throughout the region because of the massive use of agrochemicals (primarily glyphosate), the displacement of small farmers, the concentration of and decreasing access to land and deforestation.109

TLG Partners say that Paraguay offers “a refuge for investors” but this refuge is an environmental disaster, with cattle ranching being one of the main causes of deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco (Credit: FJ Capital Partners)

Sembrador Capital de Riesgo: fuelling Chile’s export fruit industry

Sembrador Capital de Riesgo SA is a Chilean private equity firm that aims to “close the gap between agriculture and the capital markets”. It was created in 2004 and has four funds totalling US$75 million invested in Chile and Colombia.110

The funds target fruit production and include Crecimiento Agrícola, Agrodesarrollo, Victus Chile and the recently created Victus Colombia, which aims to replicate “the Chilean model” in Colombia.111 In Chile, the funds are invested in farms growing avocados, nuts, citrus, truffles, cherries, pears, grapes, pomegranates, kiwi and blueberries on more than 1,376 hectares, while in Colombia, the company is looking to grow avocado, citrus, pineapple and cacao.

Sembrador has strategic alliances with Exportadora Subsole SA, one of Chile’s most important fruit exporters, and Activa, one of Latin America’s largest private equity groups, established by Larraín Vial.112 Sembrador actively tries to gain advantage from Chile’s more than 56 trade agreements, which give investors preferential access to overseas markets for fruit exports.

In relation to production systems, Sembrador focuses on using “new technologies available for precision agriculture, whether in irrigation, crop monitoring, satellite technology or any other technological means that impacts the management of the land or productive efficiency”. In terms of land, Sembrador seeks to open “new areas” for farming in “non-traditional regions”.113

Fruit production in Chile is overwhelmingly oriented towards export markets. It relies on vast monocultures, heavy use of agrochemicals and the exploitation of workers, especially seasonal labourers. Already in 2007, ANAMURI, the National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women of Chile, denounced the working conditions of seasonal workers on Chile’s fruit farms as a form of slavery.114 Part of the problem, they say, is the lack of labour contracts or hiring through sub-contractors. This translates into low salaries, long working hours and non-respect of scheduled breaks. In fact, they calculate that US$40 billion dollars of farm products are being exported annually based on workers being unfairly paid in Chile. Pesticide spraying is done without safety equipment, and fruit workers’ rudimentary living conditions are polluted and unhealthy.

In 2018, ANAMURI organised a national march to the Chilean Parliament to raise awareness about these issues as a law was being discussed to address the situation.115 There, Francisca “Pancha” Rodriguez, a member of ANAMURI, said, “This is a very important struggle. We are asking that the health problem be regulated, because workers are exposed to an excessive use of agrochemicals, with women suffering the greatest consequences including miscarriages and the birth of deformed children. In addition, we are seeing new health problems emerge from the job of cleaning, packing and packaging grapes, which means consumers are also at risk.” Investors participating in private equity funds like Sembrador’s – which include CORFO, Chile’s economic development agency, and the Interamerican Development Bank – need to be held accountable for aiding and abetting such a disastrous model.

_______________________

1Specifically five farmland funds and two private equity funds. Valoral Advisors, “2011 Global Food & Agriculture Investment Outlook”, October 2010, https://www.valoral.com/wp-content/uploads/2011-Global-Food-Agriculture-Investment-Outlook.pdf

2GRAIN, “Corporate investors lead the rush for control over overseas farmland”, 2009, https://bit.ly/2BWvggq. Includes 33 farmland funds, 11 private equity funds and six hedge funds.

3Preqin Pro, https://pro.preqin.com/discover/funds

4On 6 June 2020, the US government clarified that institutions offering individual retirement savings accounts known as 401(k)s may include private equity holdings in those accounts: The Wall Street Journal, “Private equity could be coming to your 401(k) program”, Your Money Briefing, 25 June 2020, https://traffic.megaphone.fm/WSJ1161297107.mp3. The International Union of Food Workers have produced a scathing critique of this move: IUF, “Trump’s Labor Department clears the way for private equity funds to tap directly into workers’ retirement money”, 17 July 2020, http://www.iuf.org/w/?q=node/7861 .

5Data sources: Foundation Mark for US foundations (https://foundationmark.com/#/grants); European Foundation Centre for European foundations (https://www.efc.be/knowledge-hub/data-on-the-sector/); Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute for development banks (https://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/development-bank) and sovereign wealth funds (https://www.swfinstitute.org/sovereign-wealth-fund-rankings/); Willis Towers Watson for pension funds (https://www.thinkingaheadinstitute.org/en/Library/Public/Research-and-Ideas/2019/02/Global-Pension-Asset-Survey-2019); Preqin for private equity funds. (https://www.preqin.com/insights/global-reports/2020-preqin-global-private-equity-venture-capital-report) and for hedge funds (https://www.preqin.com/DownloadInterim.aspx?d=http%3a%2f%2fdocs.preqin.com%2fpresentations%2fGlobals_Event_Presentation_-_Hong_Kong_(FINAL).pptx)

6To add insult to injury, the US government has now proposed to undo the modest reforms the Obama administration made to increase transparency in the financial industry by allowing all but the biggest hedge funds to avoid reporting their holdings. See Ortenca Aliaj, “Most hedge funds to be allowed to keep equity holdings secret”, Financial Times, 11 July 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/c68ca89c-3f9b-45f9-8205-6dbea70ed859.

7Preqin, “202 Preqin global natural resources report”, 4 February 2020, https://www.preqin.com/insights/global-reports/2020-preqin-global-natural-resources-report

8Preqin, personal communication with GRAIN, 5 June 2020.

9Some of the countries outside of North America and Europe with pension funds invested in agriculture and farmland include Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Israel, New Zealand, South Africa and South Korea. See Preqin Ltd database and GRAIN, “The global farmland grab by pension funds needs to stop,” 13 November 2018, https://grain.org/e/6059.

10In an exceptional move, in January 2020, the US banking giant JPMorgan set up its own DFI.

11See Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt, “Fees, fees and more fees: How private equity abuses its limited partners and US taxpayers”, CEPR, 11 May 2016, https://www.cepr.net/report/private-equity-fees-2016-05/ and Victor Fleischer, “The top 10 private equity loopholes”, New York Times, 15 April 2013, https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/04/15/the-top-10-private-equity-loopholes/.

12A study from 2016 found that such fees charged by general partners to the companies they’ve invested in amount to over 6% of the total equity invested by general partners on behalf of their investors. See Ludovic Phalippou et al, “Private equity portfolio company fees,” Saïd Business School WP 2015-22, April 2016, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2703354.

13Nathan Vardi and Antoine Gara, “How clever new deals and an unknown tax dodge are creating buyout billionaires by the dozen”, Forbes, 22 October 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/nathanvardi/2019/10/22/how-clever-deals-and-an-unknown-tax-dodge-are-creating-buyout-billionaires-by-the-dozen/#514d639d1861

14Preqin, “2020 Preqin global private equity and venture capital report”, June 2020, https://www.preqin.com/insights/global-reports/2020-preqin-global-private-equity-venture-capital-report.

15Jonathan Ford, “The real ‘Money Heist’ is taking place in private equity”, Financial Times, 21 June 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/96383fde-78a5-428c-b401-6b5c1fd6b925.

16Ludovic Phalippou, “An inconvenient fact: Private equity returns & the billionaire factory,” SSRN, 15 June 2020, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3623820.

17Sarah Anderson, “Toys ‘R Us worker: Wall Street billionaires should not be making money by putting people out of work”, Inequality.org, 9 December 2019, https://www.commondreams.org/views/2019/12/09/toys-r-us-worker-wall-street-billionaires-should-not-be-making-money-putting-people.

18Appelbaum and Batt, op cit.

19See Carmela Mendoza, “Key themes for Europe PE legislation in 2020”, Private Equity International, 14 January 2020, https://www.privateequityinternational.com/key-themes-for-europe-pe-legislation-in-2020/ and Deveboise & Plimpton, “European funds comment: Looking ahead to 2020 in Europe”, 10 January 2020, https://www.debevoise.com/insights/publications/2020/01/looking-ahead-to-2020-in-europe.

20See Shanti Divakaran, “Survey of the Kenyan private equity and venture capital landscape”, World Bank, 1 October 2018, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/820451538402840587/pdf/WPS8598.pdf; Alexei Bonamin et al, “Private equity in Brazil: market and regulatory overview”, Thomson Reuters, 1 February 2020, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/0-504-1335. It is worth noting that China has just allowed insurance companies to invest in private equity. See China Economic Review, “China scraps equity investment restrictions for insurance funds”, 16 July 2020, https://chinaeconomicreview.com/china-scraps-equity-investment-restrictions-for-insurance-funds/.

21Appelbaum and Batt, op cit.

22See GRAIN, “Responsible farmland investing? Current efforts to regulate land grabs will make things worse”, 22 August 2012, https://grain.org/e/4564 and “Socially responsible farmland investment: a growing trap”, 14 October 2015, https://www.grain.org/e/5294 for a deeper discussion of this.

23GRAIN, “Pension funds: key players in the global farmland grab”, 20 June 2011, https://grain.org/e/4287 and GRAIN, “The global farmland grab by pension funds needs to stop,” 13 November 2018, https://grain.org/e/6059.

24Rede Social de Justiça e Direitos Humanos, GRAIN, Inter Pares and Solidarity Sweden-Latin America, “Foreign pension funds and land grabbing in Brazil”, 16 November 2015, https://www.grain.org/e/5336, followed by further reports available on www.grain.org.

25UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust, 990 Form for 2017, https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/900424876/201833199349302778/full. The US$400 million may seem like a drop in the bucket of UAW’s US$57 billion medical care trust fund. But it is almost one-third (29%) of their allocation to natural resources, which represents 2.5% of their portfolio – a standard allocation level for pension funds.

26Black River Asset Management was originally Cargill’s own private equity firm. It was then spun off as Proterra. Proterra is an independent firm, but Cargill remains invested in it.

27As of September 2019, according to Preqin Ltd.

28Ben Butler, “Macquarie pursues US firm Amerra Capital over $40m ‘fraud’”, The Australian, 25 April 2019, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/financial-services/macquarie-pursues-us-firm-amerra-capital-over-40m-fraud/news-story/367d7bac5831fec3898172298f05e91a.

29Marcelo Teixeira, “Bid by US fund Amerra for Brazil sugar mill fails to win creditor approval”, Reuters, 19 November 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-sugar-m-a/bid-by-u-s-fund-amerra-for-brazil-sugar-mill-fails-to-win-creditor-approval-idUSKBN1XT1ZO.

30The trust’s annual reporting to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment is erratic about its farmland holdings. In 2017 and 2018, it reported holding farmland in its portfolio. In 2019, it reported it had none. In 2020, it reporting holding farmland again.

31See the slides for Chapter 8 made available as a companion to Ludovic Phalippou’s book, “Private equity laid bare”, at http://pelaidbare.com/ppt/.

32See NCH Capital’s overview of its operations: http://oldwww.ccpit.org/Contents/Channel_61/2010/1115/277453/onlineeditimages/file71289785378007.pdf

33The loans were made to Trittico Holdings Ltd (2009 and 2014) and ATS Agribusiness (2013). The equity investment was made into Cayman Islands-based NCH Agribusiness Partners II LP.

34The joint venture partner was LU Invest, a company of the Agrolats Group of Latvia, and the Ukrainian joint venture with NCH is LLC Golden Sunrise (Agro).

35EBRD documents state that the loans were specifically to be used by the Cayman Islands companies to finance NCH’s farming operations in the Ukraine. See https://www.ebrd.com/downloads/board/090325.pdf and http://www.ebrd.com/downloads/board/BDSM1404w.pdf.

36The above information was provided in email communications with the representatives of the Agrolats Group, on behalf of the owner of the company Vitauts Paškausks, in July 2020. The story has also been reported on by the Latvian news agency Pietiek and The Baltic Course. See “Latvijas uzņēmēju ‘izreiderēšana’ Ukrainā: ‘NCH Capital’ pārņēmis varu uzņēmumā, tiesājies pats ar sevi un uzvarējis”, Pietiek, 13 July 2020, https://pietiek.com/raksti/latvijas_uznemeju_izreideresana_ukraina_nch_capital_parnemis_varu_uznemuma,_tiesajies_pats_ar_sevi_un_uzvarejis and “Chairman of the Board of ‘Agrolats Holding’: Latvian agricultural holding is trying to save its Ukrainian investments from a respectable American investment fund”, Baltic Course, 8 July 2020, http://www.baltic-course.com/eng/direct_speech/?doc=157205.

37“NCH Capital farmland exit signals broader sales effort in Romania,” AgriInvestor, 31 March 2020, https://www.agriinvestor.com/nch-capital-farmland-exit-signals-broader-sales-effort-in-romania/.

38“ARGAȚII”, RISE Moldova, 19 May 2020, https://farmlandgrab.org/29587.

39Ibid.

40Under the new law, foreign entities are still prohibited from purchasing farmland, but it becomes possible for Ukrainian individuals and companies to acquire much larger areas of farmland, up to 10,000 ha by 2024, making it easier for NCH Capital to extend its control over farmland through leases, joint venture operations and its banking activities. There is also talk of a referendum on foreign ownership of farmland that could be held at a later date. See Oakland Institute, “IMF leverages COVID-19 economic fallout to create a land market in Ukraine despite widespread opposition,” 21 May 2020, https://farmlandgrab.org/29646.

41US Office of Public Affairs, “US Secretary of Commerce Penny Pritzker announces completion of $1 billion loan guarantee to Ukraine,” 28 September 2016, https://2014-2017.commerce.gov/news/secretary-speeches/2016/09/us-secretary-commerce-penny-pritzker-announces-completion-1-billion.html.

42US Embassy in Ukraine, “US Secretary of Commerce Penny Pritzker to visit Ukraine and Germany,” 23 October 2015, https://ua.usembassy.gov/u-s-secretary-commerce-penny-pritzker-visit-ukraine-germany/

43“KKR to invest $200m in Ethiopian flower business”, Ethioinvest.com, June 2014, http://ethioinvest.com/news/item/125-http-www-ventures-africa-com-2014-06-kkr-to-invest-200m-in-ethiopian-flower-business.

44Imani Moise, “KKR exits African investment”, Wall Street Journal, 20 December 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/kkr-exits-african-investment-1513774577.

45Data is from Preqin Ltd.

46“Coller FAIRR protein producer index 2019”, Farm animal investment risk and return initiative, Jeremy Coller Foundation, 2020, https://www.fairr.org/article/coller-fairr-protein-producer-index-2019/.

47“CDC Group pumps $100mln into Helios Investors IV,” Agence Ecofin, 7 July 2020, https://www.ecofinagency.com/finance/0707-41587-cdc-group-pumps-100mln-into-helios-investors-iv

48“Spotlight on OPIC Impact Award winners: Helios Investment Partners”, OPIC Blog, 26 March 2014, https://www.heliosinvestment.com/uploads/files/Spotlight-on-OPIC-Impact-Award-winners-Helios-Investment-Partners_1.pdf. In 2018, OPIC was replaced by the International Development Finance Corporation.

49See the report from the French National Assembly, 8 June 2011, http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/pdf/amendements/3406/340601552.pdf.

50“Helios acquires African fertilizer business in $200 million deal,” Financial Nigerian, 1 August 2017, http://www.financialnigeria.com/helios-acquires-african-fertilizer-business-in-200-million-deal-news-1397.html

51See the company’s website: https://www.solevogroup.com/fr/accueil/.

52See US Congress, “HR 2237 – To promote the strengthening of the private sector in Egypt and Tunisia”, 112th Congress (2011-2012), https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/2237/text

53See Fairfax, “Proposed strategic transaction between Helios Holdings Limited and Fairfax Africa Holdings Corporation”, 10 July 2020, https://www.fairfaxafrica.ca/News/Press-Releases/Press-Release-Details/2020/Proposed-Strategic-Transaction-Between-Helios-Holdings-Limited-and-Fairfax-Africa-Holdings-Corporation/default.aspx.

54Loch Adamson, “SilverStreet Fund focuses on agriculture in Africa,” Institutional Investor, 28 May 2010, https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b150qftv679j7c/silverstreet-fund-focuses-on-agriculture-in-africa.

55See the 2012 audited financial statements of the SilverStreet Private Equity Strategies SICAR, which is the entity that holds the commitments for the Silverlands Funds, available at the Luxembourg business registry: https://www.lbr.lu/.

56The annual “external charges” of the fund, which include the priority profit share and numerous other fees such as accounting and custodian fees, vary from US$4 million to US$5.5 million. See the annual accounts of the SilverStreet Private Equity Strategies SICAR, available at the Luxembourg business registry: https://www.lbr.lu/.

57The company is Crookes Brothers Limited. See its financial statement for 2020 here: https://www.cbl.co.za/investors/financial-results/.

58The total advisory fees paid to SilverStreet Capital Agricultural Advisors and SilverStreet Capital LLP by both the maiden Silverlands Fund and the followup Silverlands Fund II for 2018 was roughly US$7.6 million.

59Silver Street Capital, “Creating value and a positive impact in African agriculture”, June 2019, https://www.peievents.com/en/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Day-1-11.30-Wise-Chigudu-ESG-Case-Studies.pdf.

60See the articles of association and the 2018 audited financial statements for SilverStreet Private Equity Strategies SICAR, available at the Luxembourg business registry: https://www.lbr.lu/. The articles of association indicate that the general partners paid in US$2,001 as initial capital.

61Silverstreet Capital, “2019 annual impact and ESG Report: The Silverlands funds”, https://www.silverstreetcapital.com/s/FINAL-short-2019-Annual-ESG-Review-med-res.pdf.

62The Foundation has US$50 billion under management. Of that, US$500 million (1%) is tied up in private equity, according to Preqin Ltd.

63Louisa Burwood-Taylor, “Gates Foundation invests in dairy tech Stellapps $14m series B, first in India”, Agrifunder News, 31 May 2018, https://agfundernews.com/gates-foundation-invests-in-dairy-tech-stellapps.html

64Data is from Preqin Ltd

65“Abraaj Capital quitte le tour de table de l’entreprise Gallus”, Agence Ecofin, 7 February 2014, https://www.agenceecofin.com/entreprises/0702-17415-tunisie-abraaj-capital-quitte-le-tour-de-table-de-l-entreprise-gallus.

67Wanjohi Githae, “Brookside takes over Rwanda’s top beverage firm”, Daily Nation, 1 October 2016, https://www.nation.co.ke/kenya/news/brookside-takes-over-rwanda-s-top-beverage-firm-1244302

68Gates Foundation Trust, “2018 Annual Tax Return, Form 990-PF: Return of Private Foundation”, https://www.gatesfoundation.org/-/media/GFO/Who-We-Are/Financials/2018-BMGFT-Form-990-PF-For-Public-Disclosure.ashx.

69Omnivore, “Impact”, https://www.omnivore.vc/impact/.

70Debolina Biswas, “Doodhwala founders reveal how their startup uses technology to disrupt the Indian milk market”, Your Story, 14 May 2019, https://yourstory.com/2019/05/startup-milktech-doodhwala-bengaluru.

71Bhumika Khatri, “Exclusive: Doodhwala vendors file FIR against ‘absconding’ founders for unpaid dues”, Inc 42, 17 November 2019, https://inc42.com/buzz/exclusive-doodhwala-vendors-file-fir-against-absconding-founders-for-unpaid-dues/ and Mr. Manjunath of Erden Creamery, personal communication with GRAIN, 26 July 2020.